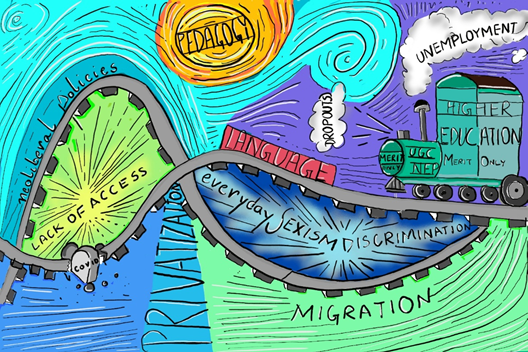

Policies and Beyond: Looking into the Future of Higher Education.

Author: Nupur Jain

The long-awaited national education policy 2020 has been in the discussion for a few years now. It envisages a unique trajectory with its overall hopeful and positive tone and is bound to have a long lasting impact on the education sector in India. It plans on spending 6 % of India’s GDP. The policy’s silent, non-debatable approval by the cabinet happened amid unprecedented pandemic, economic crisis, and increased cost of living for common people. This has raised several questions about the government’s real commitment to a robust, impactful policy framework and the necessary measures required for its proper implementation..

We live in unprecedented times of gender parity with equal number of girls and boys pursuing higher education. Educational institutions have proliferated in numbers and the problem of ‘access’ is not as urgent as it was some decades ago. However, we must ask what happens when we go beyond questions of mere access and parity. “The Research Study to Further Gender Equality in Higher Education”, a project by Savitribai Phule Pune University and Brunel University discusses this very pertinent question, among other emerging themes. This blog particularly looks at the shifts in policies on one hand, and in the national, socio-political and cultural context on the other; and how it overlaps with significant ramifications for women and other marginalized groups. At its heart lies the very meaning of education which seems to have shifted with changing policies and socio-political landscape of the country. This blog attempts to map some critical moments in the history of policy reforms from the vantage point of higher education.

In 2020, when the New Education Policy 2020 was introduced, it called for deeper introspection in many areas. What is the origin of this policy? Where has it come from? What are the shifts that have occurred over the years in regards to the policy?

But let us go back a little first…-

Newly independent India was reeling under massive illiteracy when the Union government established the University Education Commission in 1948 (1948–1949), also popularly known as the Radhakrishnan Commission, laying great stress on education for agriculture and its improvement. It created the University Grants Commission in 1953 (got statutory status in 1956) to advise on regulation of university education, scholarships/fellowships and grants.

-

The University Education Commission report remarked that only women can educate the future generations. In 1957, the “Education Panel of Planning Commission” in Poona recommended that a suitable committee should be appointed to look at education of girls at all stages of their lives, and to examine whether the present system helps them to lead happier lives. In 1958, a national committee on Women’s Education was introduced by the Ministry of Education, under the guidance of chairperson Shrimati Durgabai Deshmukh. The committee focused on adult women relapsed into illiteracy and in need of financial independence. Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, who inaugurated the committee stated that while women should make their presence felt in the public sphere, her “greatest profession is that of a home-maker.” Education in practice became a way to maintain traditional hierarchies under the garb of progress and modernity. This points to how in a newly independent country like India, higher education was an effective conservative tool to restore the ‘glorious traditional culture’ of the country.

-

At the end of the third five-year plan, the Education Commission (1964-66) was formed under the leadership of Dr. D.S. Kothari. The Kothari commission laid special emphasis on the newly independent status of the country, the idea of democracy, justice, liberty, equality, fraternity, and the Indian culture. It laid great emphasis on a science-based education that is in coherence with Indian culture and values. It was focused on the idea of ‘nation’ through education. The report also laid emphasis on establishment of major universities and its governance.

-

In 1968, Indira Gandhi’s government announced the foremost National Policy on Education, based on the report and recommendations of the Kothari Commission (1964-1966). This was the first attempt towards establishing a certain homogeneity across India, with the goal of bringing national integration. This effectively meant that the government was considering a ‘radical restructuring’ of the system. It focused on training and development of teachers, the “three language formula” (Hindi, English and regional language), introduction of Hindi as national language to foster a common identity among Indians, promotion of Sanskrit language as heritage of India.

-

With rapid changes in the political economy of the country, these years witnessed the influx of previously excluded castes and classes alongside those who had already comfortably occupied space in higher education. A new heterogeneity was making its way into the otherwise stable and set ways of university education system. The higher education system was getting slowly destabilized with the entry of women and first-generation learners from marginalized groups.

-

The Report of the Committee on the Status of Women in 1974 (Towards Equality, 1974) placed women’s education within the broader framework of developmental issues in the country. It was the first committee to take the most comprehensive review on women’s status after independence.

-

The National Policy of Education (1986) took this vision further to underscore the role of education in overcoming social disparities for women.

In the years to come, higher education transformed drastically. After a gap of almost two decades, the second NPE was introduced in 1986.

-

The focus shifted on increasing enrolment in higher education, providing equal access to all, increase quality of education. The new policy called for a special emphasis on eliminating disparities and providing equal educational opportunities for women, scheduled tribes, scheduled castes. It demanded more scholarships, adult education, social inclusion, training of more teachers from scheduled caste background. This was the first time, when Women Studies as a discipline was promoted; although in the eyes of the government, it meant promotion of courses like home science, music, tailoring, embroidery, cooking, etc.

-

Soon after, it was felt that the policy needed to be reviewed. After careful deliberations, the PoA (Programme of Action) 1992 was designed to conduct common entrance examination on all India basis for admission in professional and technical programs. The objective was to correct social and regional imbalances and bring equal representation from diverse regions.

-

National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) was constituted by UGC in 1994 to regulate and set the standards for the academic evaluation of institutions.

-

Until this point, most privately run colleges were eligible for getting grants from state governments, which means that higher education was still affordable for the masses! But following the NPE 1986, this changed and private colleges started coming up. Public sector funding went down, and neoliberalism allowed private institutions to alter the quality, access, affordability of higher education. In a country where education has, for the longest time, remained the prerogative of the high castes, the question of achieving uniformity of education across social groups loomed large.

-

In August 1990, the government announced 27% reservations for Other Backward Castes (OBCs) in central government services and public sector units, by implementing the recommendations of the landmark Mandal report. The second half of the Mandal Commission’s recommendation was to provide reservations to OBCs in central educational institutions (which was realized only much later in 2006). This led to widespread protests across the country and a Delhi University student immolated himself, becoming the face of anti-Mandal movement. This moment also saw the genesis of the Ram Mandir narrative in public sphere. In September 1990, L K Advani began the Rath yatra, passing through hundreds of villages and cities across the country. These years left a long-lasting impact on the socio-cultural and political fabric of the country.

-

Years later in 2016, the Committee for Evolution of the New Education Policy (NEP), chaired by Mr. T. S. R Subramanian submitted a report proposing a renewed education policy. The Committee observed that there has been a steep rise in teacher shortage, absenteeism, and grievances. It recommended ITC for teacher training, adult literacy, and online skills-based courses. It also recommended that UGC and the AICTE be replaced by “National Higher Education Promotion and Management Act (NHEPMA).”

-

Nearly three decades after the last policy, the newly proposed National Education Policy (NEP) 2016 was released, requesting suggestions from the public. It focused on various aspects like access, quality of education, curriculum, teacher development, skill development and employability. In June 2017, the government constituted the K. Kasturirangan committee which submitted its Draft NEP in 2019, based on the inputs provided by the Subramanian report, which had come out earlier that year.

-

In 2019, the New Education Policy was released, accompanied by series of public consultations. This draft NEP 2019 addressed questions of curriculum, logical thinking, discussion-based learning, pedagogy, etc. In 2020, the union cabinet introduced NEP 2020, thus making it the first policy of the 21st century to substitute the 34-year-old national policy. It heavily focuses on holistic multidisciplinary overhaul of the education system, proposing major changes like dismantling of the UGC, AICTE (All India Council for Technical Education), opening up of higher education to foreign universities. It recommends a ‘5+3+3+4’ education structure plan, which means undergraduate degree will be a four year multidisciplinary programme with multiple entry-exit options. It attempts to bridge the gap between curricular, extra-curricular, co-curricular activities amongst major disciplines like arts / humanities, sciences, vocational courses and proposes that all single stream colleges and institutions must phase out and become multidisciplinary by 2040. It has also discontinued the M Phil programme.

It is worrisome that the NEP will provide a nod to these largely homogenous and blanket recommendations in a country with vast heterogeneity and inequality. This is evident in, for example, the proposal that students can choose to exit from a programme at any point during their education and get a certification for it instead. What does this imply for students who are, one, entering the job market in times of declining decent work opportunities and jobless growth , and two, are already at the very margins of higher education, having barely managed to step into it? Further, neoliberal policies and the withdrawal of state from the sector has pushed for more private investment in higher education, leading to questions about affordability and quality of education. With a huge knowledge-job disparity, lack of resources, and disproportion between stated and actual public spending targets on higher education, we know far too little today about how this new ambitious policy is going to impact women and students from marginalized backgrounds.

Higher education has become, now more than ever, a site of political upheaval. One must ask whether we have moved towards a more open, a more inclusive system of higher education for all, with ideas of social justice at its heart. This fundamentally means asking whether institutional cultures have radically transformed. Unfortunate incidents involving the institutional murders of scholars like Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, for example, point to the ways in which our institutional cultures are far from being inclusive and just. Today university going students find themselves behind bars instead of inside classrooms, our campuses are filled with anti-intellectual campaigns, and it is increasingly difficult to defend the idea of transformative. In this backdrop, a policy that focuses on being ‘rooted in Indian-ness’ should force us to ask who is imagined as ‘Indian enough’? And who is imagined to be a threat for the nation? To lay out the policy as the future of a modern India without honoring constitutional values and ideas of secularism is testimony to the fact that it is, by its very design, not meant to engage with the fundamental ethos of equality and freedom.

Many questions remain unanswered. One must then, out of sheer civic responsibility, question whether the enthusiastic overhauling of the education system as promised in our policy, is cognizant of the contexts in which it is formulated.

Artwork designed by: Sayali Shankar

References:

- Deshpande, S. (2016). Higher Education An Uncertain Policy Process. Economic & Political Weekly, 37-40.

- Roy, K. (2020, August 28). NEP 2020 implementation and timeline worries. Retrieved from Frontline: https://frontline.thehindu.com/cover-story/timeline-worries/article32305885.ece

- Ministry of Human Resource Development. (2016). National Policy on Education 2016: Report of the Committee for Evolution of the New Education Policy

- University Grants Commission. (2008). Higher Education in India: Issues related to Expansion, Inclusiveness, Quality and Finance

- Suhag, R. (2016). Rethinking education: The draft NEP 2016, PRS India

- https://prsindia.org/policy/report-summaries/national-education-policy-2020

- Ministry of Education. (1959). Report of The National Committee On Women’s Education.

- NCERT. (1970). Vol I: General Problems, Education and National Development.

- https://soe.unipune.ac.in/studymaterial/rupaliShewaleOnline/commissions%20and%20recommendations.pdf

- Ministry of Education. (1962). Volume 1, The Report of the University Education Commission

- https://www.education.gov.in/en/nep-new

- http://journal.iujharkhand.edu.in/Dec-2020/The-Significant-Shift.html

- John, M. (2019). Sexual Violence 2012-2018 and #MeToo, The India Forum.

https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/sexual-violence-2012-2018-and-metoo